This article is continued from the March/April 2024 issue of Viking.

By Emma Enebak

How Norwegian architecture firm Snøhetta rose from humble beginnings to revolutionize contemporary ideas of architecture and design.

In a remote area of Central Norway, there is a beautiful mountain range called Dovrefjell. Significant for many reasons, including its sacred symbolism in Norse mythology, the mountain range also harbors Norway’s 24th tallest mountain peak, Snøhetta. Standing at about 7,500 feet, the misty, snow-capped mountain is certainly a marvel. But it is far from being Norway’s tallest or most famous peak.

Yet, of all the mountains in Norway (and there are estimated to be more than 300), the internationally esteemed architecture firm, Snøhetta chose to share its name. The Norwegian-based transdisciplinary practice refers to its mountainous namesake as “beautiful, remote and historically important.” By this standard, it is not scope or size that makes the mountain significant, but rather its location and unique story.

A Tale as Old as Time

The Dovrefjell mountain range is one of the oldest and most important symbols in Norwegian history. In Norse mythology, Dovre is said to be the location of Valhalla, the land where fallen warriors rest in their afterlife. This almost heavenly symbolization carried onward to some of Norway’s earliest settlers, who were Stone Age hunters that depended on the area’s reindeer population for survival. Considering it to be the earliest association to their ancestors, Norway’s Constitutional fathers honored Dovre in the drafting of the Constitution in 1814. The phrase “enig og tro til Dovre faller,” or “united and loyal until Dovre falls” concludes the Constitution as a show of Norway’s strength and sturdiness.

Snøhetta’s architectural and design projects are no different. Primarily shaped by the natural environments and cultural contexts they are built within, each of Snøhetta’s structures tells a unique story—built to be an extension of, rather than a disruption of its surroundings. Adaptable to any language, terrain, altitude or cultural purpose, Snøhetta builds as if holding up a mirror to its environment, creating projects that reflect what is important to the people who will inhabit them.

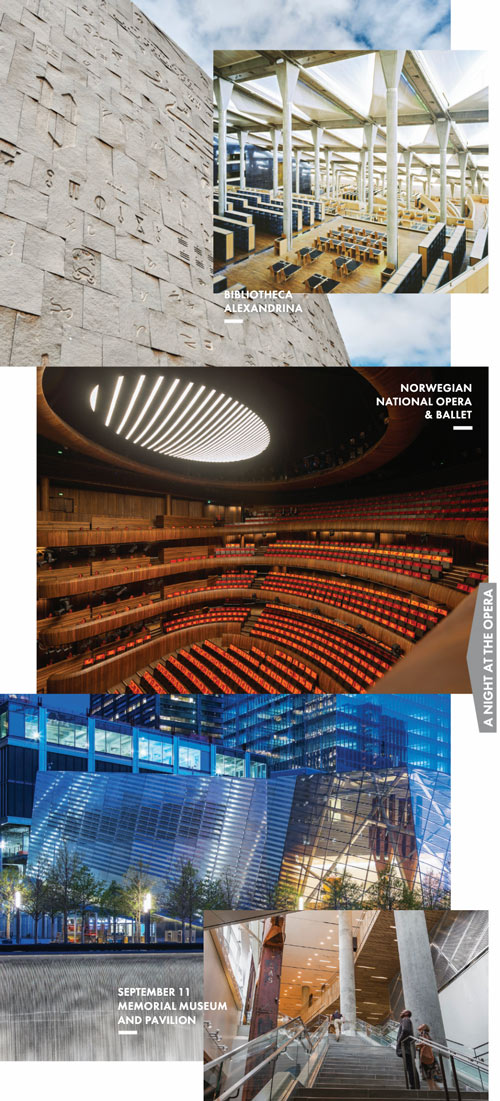

With these principles in mind, Snøhetta tackles a wide range of projects, from those as large-scale as the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Egypt, to those as small-scale as the Vulkan Beehives in Oslo—each receiving the same care and attention to detail. Reminiscent of its namesake, it is not the scope or size of project that is of greatest importance to Snøhetta, but rather the opportunity to connect societies with the world around them. As a byproduct, the firm’s diverse projects span the whole globe, and it is likely that even those who have never heard of Snøhetta will recognize more than one of them. In just 34 years of operation, its touch can be seen across six continents, and its work has quickly become among the most sought-after in the world.

But 34 years ago, Snøhetta was just six people meeting above a beer hall.

Humble Beginnings

Snøhetta’s first offices were located above a beer hall in Oslo called Dovrehallen (The Hall of Dovre), notably named for the Dovrefjell mountain range. Among these early members was cofounder Kjetil Trædal Thorsen, who like his five fellow architects, was still under 30 years old. The young team’s distinctively collaborative spirit—at the time somewhat of an anomaly in the architecture world—is largely responsible for landing them their first major international commission. In 1988, a competition was announced for the restoration of an ancient library founded by Alexander the Great in Alexandria, Egypt more than 23,000 years ago. Thorsen, who had already entered the competition, was soon thereafter put into contact with a young architect named Craig Dykers, who owned a small private firm in Los Angeles. The two felt an instant creative spark, and eventually decided to collaborate on the project along with a group of architects from Norway and the U.S. While still a barely established firm split across two continents, the team’s proposal placed first among more than 500 entries for the commission of the library—an achievement that launched Snøhetta not just into existence, but into international recognition. Dykers quickly relocated to Oslo and alongside Thorsen, officially established Snøhetta, setting to work on what would over the course of 13 years become known as the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Their success soon earned them commissions to the Norwegian National Opera & Ballet in 2000 and the National September 11 Memorial Museum and Pavilion in 2004. Snøhetta now has over 350 employees from 40 countries, and holds studios in Oslo, New York City, San Francisco, Innsbruck, Paris, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Adelaide and Melbourne.

The collaborative attitude largely responsible for Snøhetta’s existence has never left the firm. A visit to one of their studios will reveal an intentionally open and nonhierarchical space, in which co-founders Thorsen and Dykers sit at workspaces identical to everyone else’s. Each studio also contains a commercial kitchen in which all employees eat lunch together across long, open dining tables. This collectivist approach is meant to encourage the free flow of information and an open dialogue between employees, across all disciplines and job titles. As Dykers told The New Yorker in 2013, “anyone can suggest anything about anything.” This held true as Snøhetta began expanding into multiple disciplines, including landscape, art, interior, graphic and digital design. As projects are constructed, the conventional idea of “profession” is thrown out the door, with employees thinking across disciplines and contributing based on their creative intuitions. This may be part of why it is difficult to define Snøhetta’s style. Rather than conforming to a rigid protocol, each project is a testament to the collaboration of diverse creative minds. And despite Snøhetta’s astounding success, its projects continue to reflect this modest, egalitarian attitude—built not to be spectacles, but to be accessible and open spaces for everyone to enjoy. A look at some of Snøhetta’s most acclaimed works will reveal no less.

Officially inaugurated in 2002, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina is an 11-story tilted cylindrical building resting along Alexandria’s ancient harbor. The striking historical and cultural relevance of the library was not lost on Snøhetta, who saw its commission as an opportunity to build an international reawakening of Mediterranean knowledge and culture. Designated as an intellectual gathering place for students, researchers and the public, the library can hold up to 4 million volumes of books and can be expanded by the use of compact storage to hold up to 8 million. Its vast reading room is designed to comfortably fit up to 2,000 readers at a time—the largest of its kind worldwide. The library’s distinct circular shape echoes this accessibility of knowledge, intended to signify the cyclical flow of knowledge across history, simultaneously embracing the past, present and future.

In a collaboration between Norwegian artist Jorunn Sannes and Norwegian sculptor Kristian Blystad, the structure was outfitted in nearly 20,000 square feet of hand-carved stone. Across this stone can be seen 4,000 unique letters and symbols from various alphabets, mathematical and musical notations, Braille and barcodes, spanning 10,000 years of human history. The symbols are intentionally ordered at random, so as to represent an amalgamation of diverse human interests and understandings. Since its opening, the library has become a global symbol of knowledge, peace, citizenship and democracy, so beloved that amid unrest in Egypt back in 2011, thousands of Alexandria’s youth banded together to protect the building against vandalization.

Norwegian National Opera & Ballet—Oslo, Norway

The Norwegian National Opera & Ballet was designed around the intention of reclaiming Oslo’s historically industrial waterfront as a public space for recreation and community. Perhaps the building’s most recognizable feature could be its slanted, walkable plaza, which leads directly down to the Oslofjord and effectively restores the stretch of harbor space to the public. Honoring a historic Norwegian custom known as allemannsretten, or “the right to roam,” the building was designed to be just as much a landscape as a work of architecture, with walkable exteriors and keyless interiors that invite non-opera or -ballet attendees to roam freely. Today, the white carrara marble-covered roof regularly holds public concerts and simulcast viewings of the operas happening inside the main theater.

Inside, the building’s main hall nods to classical theaters of the past, with its distinct horseshoe shape and light oak interiors. Besides its three performance stages, the space also houses one of Norway’s largest public art collections, featuring eight projects by 17 different artists. The building’s doors are unlocked and open to the public 24 hours a day, promoting an accessibility of art and culture that is extremely rare, and uniquely Norwegian.

A Night at the Opera

Experience the magic of the Norwegian National Opera & Ballet by planning your own visit. Conveniently located along the beautiful Oslofjord, a trip to Norway’s capital city is not complete without a tour of the famous structure. Catch a show from the venue’s packed 2024 schedule, which includes classic productions like “Madama Butterfly,” “Swan Lake” and “La Traviata,” as well as uniquely Nordic expressions including choreographies by Mats Ek and vocalist Kajsa Balto’s “Sámi Juovllat–Samisk Jul.” If attending a show is not your fit, you are still welcome to roam the wondrous grounds of the Norwegian Opera & Ballet, which is free and open to the public. Stop in to appreciate one of Norway’s largest public art collections or peer through the building’s transparent walls at “The Workshop,” where opera and ballet staff construct costumes, sets and various elements of stage production.

9/11 Memorial Museum and Pavillion—New York City, New York

In 2004, Snøhetta achieved its first American commission to design an entrance pavilion to the September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City, designed by architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker. Constructing what was to be the only building on the sacred grounds of the memorial was a defining challenge for the firm, with nearly 10 years spanning the initial commission and the building’s official opening in 2014. Snøhetta diligently approached the project as if building a bridge between two worlds, wrestling with the complicated transition between the bustle of city life and the uniquely spiritual experience of the memorial.

With its crystal, stainless steel complexion and striking geometric shape, the pavilion building appears as if it fell from the sky, jutting down into the plaza at an almost precarious slant. Its unmistakable shape is meant to act as a threshold, providing a space for pause and reflection as visitors are led from the sunlit museum down to the shadowed memorial. Within the atrium, two large columns salvaged from the original twin towers rise to the glass ceiling, marking the site with their physical memory. The transparent walls of the atrium allow passersby to peer in and visitors to peer out, personifying the mental transition that occurs once inside. However, with its artfully striped façade, the exterior of the pavilion still manages to blend with the urban landscape surrounding it—a building that is both within and outside the everyday hustle of New York life.

Vesterheim Commons—Decorah, Iowa

Vesterheim is a National Norwegian-American Museum and Folk Art School located in Decorah, Iowa. With a core mission of community-building, Vesterheim tapped Snøhetta in 2018 for the construction of a common gathering space for Norwegian-Americans to connect and share stories. Completed in fall 2023, the result is an 8,000 square-foot building known as The Commons, situated as an anchoring point between Vesterheim’s Heritage Park and Decorah’s main street.

When constructing The Commons, Snøhetta set out to align with the time-honored Norwegian craft tradition of using humble, locally sourced materials. Incorporating timber from nearby Albert Lea, Minnesota and brick sourced from Adel, Iowa, the building stands as a testament to the culture and resources surrounding it and aims to seamlessly blend with Decorah’s natural landscapes. A stunning viewpoint is provided between the ground floor and the second floor through a wooden oculus opening, which bathes the lobby in light. On the upper level, flexible gallery space harbors a revolving collection of cultural artifacts and artworks. The building is now recognized as a national cultural gathering space, drawing in visiting groups from across the country.

Sustainability Efforts

As Dykers told Architectural Digest in 2016, Snøhetta doesn’t see its buildings as separate from the earth. This is a fitting way to describe the firm’s focus on environmental sustainability, an area in which they are constantly pushing boundaries. Inspired by the United Nations’ 1987 Brundtland Commission, which defines sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs,” Snøhetta has strived to meet these qualifications from the beginning. On a project-by-project basis, the firm carefully considers such elements as material sourcing, energy management, water conservation, carbon and emissions control and waste control. The impact of these considerations can be seen globally. In preparation to build the Norwegian National Opera & Ballet, Snøhetta organized a large-scale environmental cleanup of the site, restoring the Oslofjord to its cleanest state in over 100 years. Recently, Snøhetta was granted the 2023 UN Global Climate Action Award for their work on Powerhouse Kjørbo, Norway’s first energy-positive office building and likely the first renovated energy-positive building in the world. Through the use of unique ventilation systems and the harnessing of natural power sources, the building will produce more renewable energy than it will consume over its lifetime.

Snøhetta achieved a similar feat in Meløy, Norway in 2019 with the construction of SVART—the world’s first energy positive hotel. Situated above the Arctic Circle, SVART has set a new standard for energy consumption in Arctic climates. Strategically constructed in a circular shape so as the best exploit the energy of the sun throughout the seasons, the hotel reduces its yearly energy consumption by 85% while simultaneously producing its own energy. Stretching out into the clear waters of the Holandsfjord, the hotel is not only a groundbreaking achievement in environmental sustainability but makes for a truly breathtaking Arctic viewpoint.

What’s Next?

Snøhetta is currently amid multiple projects, notably including the Royal Diriyah Opera House in Saudi Arabia, the Shibuya Upper West Project in Tokyo and the reconstruction of the famous Cannes Boulevard in France, which are all scheduled to wrap up by 2028.