Author and translator Barbara Sjoholm on uncovering and uplifting the undertold stories of Scandinavia’s Indigenous people

An abridged version of this conversation appeared in the Jan/Feb issue of Viking. Here is the complete interview.

BY EMMA ENEBAK

In the opening of her 2007 book, “The Palace of the Snow Queen,” author and translator Barbara Sjoholm describes the “blue hour” in northern Scandinavia: “when the slate-colored snow looks colder than white.” Well above the Arctic Circle at the start of winter 2001, Sjoholm’s four-month journey through the North was in part provoked by her Norwegian friend Ragnhild Nilstun’s insistence that “what’s more fascinating about the North is not the light, but the dark,” or the blue light that prevails in the absence of the sun.

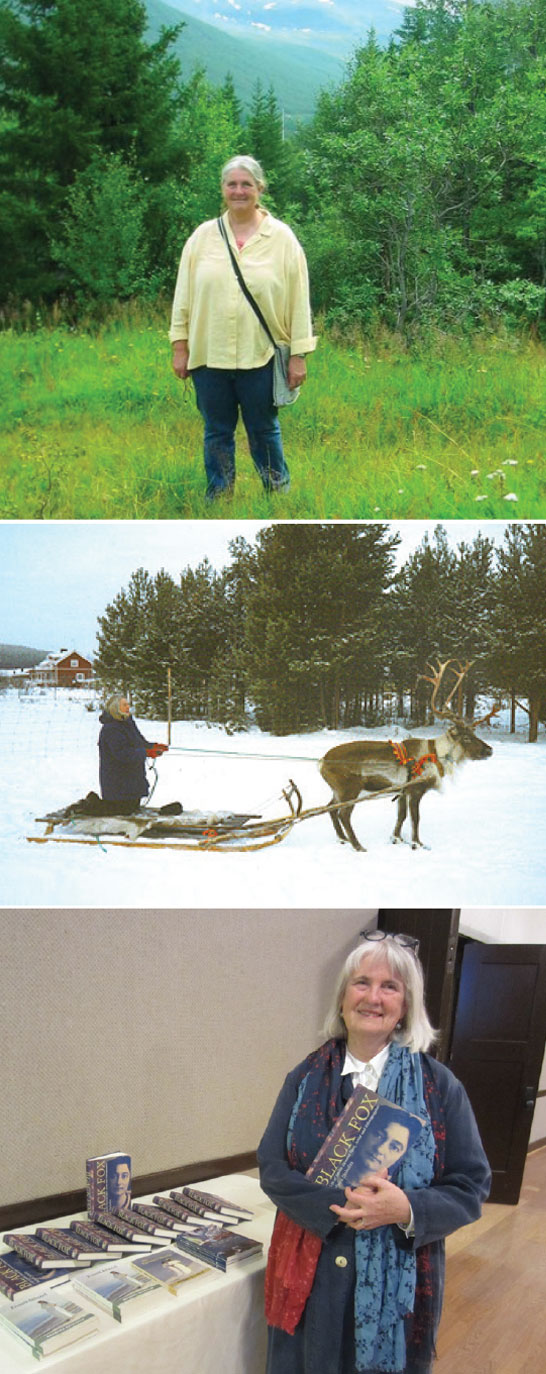

From above: Sjoholm on a research trip to Tromsdalen,

Norway, in 2009; Sjoholm reindeer sleds on a trip to

Jukkasjärvi, Sweden, in 2001; Sjoholm signs copies of “Black

Fox” at the Norwegian Heritage Museum in Seattle in 2017.

This journey into the blue light was also fueled by Sjoholm’s desire to learn more about the Sámi, the Indigenous people to the territory known as Sápmi, presently comprised of northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. An American of Swedish and Norwegian heritage, Sjoholm is not herself of Sámi descent, but there was something about these people and their way of life that captivated her.

During this winter trip through Scandinavia, which Sjoholm took two more of within a period of four years, she began to uncover more about the fascinating, yet relatively suppressed culture of the Sámi. Soon, Sjoholm found that “this was a way she could be useful,” merging her writing and translating talents to bring their stories to light.

Sjoholm has since published multiple works focused on the history, customs and language of the Sámi, including “By the Fire,” a 2019 translation of Sámi folktales and legends, and “From Lapland to Sápmi,” a 2023 examination of Sámi material culture. She has returned to Scandinavia almost every year for the past 20 years, to experience the rare beauty of these blue winters, and continue learning, growing and connecting with the culture she has come to respect so deeply.

We caught up with Sjoholm to learn more about her travels, her work as a writer and translator and her dedication to bringing more visibility to the Sámi culture and way of life.

Can you briefly describe your background as an author and a translator? How did you get into this line of work, and how did you discover your focus area in Sámi culture?

Briefly, eh? I have Swedish heritage. My grandmother was Swedish, and she emigrated to Illinois. I have a little bit of Norwegian and lots of Irish. I had not really grown up knowing much about my heritage, but when I was 21, a friend of mine got a job in Norway as a maid for a wealthy family in Oslo. She wrote me a lot of lyrical letters about how beautiful Norway was and said if I would come over, I could probably get a job, too.

So, I did, I went up to the mountains, Jotunheimen, and worked that summer in a souvenir shop at a hotel. I started learning Norwegian as soon as I got to Norway. I never really studied it properly, I just started talking and reading. The following summer, I got a job as a dishwasher on the Hurtigruten (Norwegian coastal express), so, I got to see northern Norway, and that really sparked my interest in learning the language better. Within a few years, I was experimenting, translating with a friend of mine who lived in Norway, and I just continued doing translation.

I had been really interested in the Sámi from early on, and I think it’s partly because I didn’t just stay in the south of Norway. I was on the boat, and we went all the way up the Norwegian coast to Kirkenes on the Russian border. I got to see that landscape, and it really appealed to me. And then later on, I made a good friend who lived in Tromsø, Ragnhild Nilstun, a writer of novels. And Ragnhild had said to me, ‘You should really come to northern Norway in the winter.’ And I said, ‘Whoa, why would I want to do that?’ She said, ‘Well, it’s beautiful. Everyone comes in the summer, no one comes in the winter.’

I took her up on it, and I actually spent four months traveling around the north of Norway from November through February. That trip led to two more over a period of about four years, and during that time, I really got to know more Sámi people and learn much more about the history of Sápmi.

I felt that that’s a way I could actually be useful, because no one was really writing much about the Sámi. There are certainly academics here and there, but the Sámi were not very well known in the United States. People kind of had outdated, stereotypical ideas about how they live—that most of them were reindeer herders, and that they were still living in tents, for instance. And I could see that so much more was happening in Sápmi, in terms of a Renaissance of culture, language and politics, and I wanted to convey that. So, gradually that became another career for me, translating from Danish and Norwegian, and also writing about my own experiences with the Sámi and the things that I’m interested in.

Were you always interested in writing, or did your writing interest come about once you found the subject you were passionate about?

I have always been interested in writing. I was a very slow reader when I started out, and I was sort of mildly dyslexic. But suddenly, when I was 8, everything got easier. I guess I was a slow developer. I think because I had been so frustrated in my efforts to read for so long, I just fell completely in love with books and went to the library all the time, read everything I could. But, like a lot of people, I didn’t get very much support for the idea of being a writer. My dad was like, ‘Yes, yes, but be sure to learn typing and maybe bookkeeping would be a good idea. Why don’t you be an English teacher?’ But I knew that there must be a lot of writers out there because the libraries were full of books. So, someone was writing them and making a living at it. And that’s what I wanted to do, too. So, I’ve been fortunate in that.

What role do you think translation plays in promoting cultural exchange and understanding?

I think it plays a large role because most Americans don’t read anything in a foreign language. We do have such a rich culture in the U.S., made up of all the people who have come here, but you miss something when you aren’t able to read about foreign cultures as well. So, I think we do rely on translators, and that’s been true for a long while. In the beginning, when Norwegians first came over, for example, they all did read Norwegian. And so, they wrote in Norwegian, and there was a Norwegian press and they would import books from Norway. But within a generation, people couldn’t read Norwegian anymore. So, they were relying on translations, even of Norwegian books, but also, they began to participate in the wider American experiment of reading books from all over the world. So, Russian, French, German, we wouldn’t be reading any of those books, Tolstoy or Balzac, if there weren’t translators translating them.

What challenges do you usually encounter while translating, and how do you overcome these challenges?

Well, every book is different, and every book has a kind of different vocabulary and rhythm. The first books I translated some years ago were all in Norwegian, because that was the language I knew best. So, when I decided that I wanted to translate the [Danish] work of Emilie Demant Hatt, I encountered immediately a lot of challenges. Danish has a kind of different rhythm, you know, the sentences were much longer, so I had to break them up. But there were also a lot of words I was unfamiliar with, having to do with reindeer herding from 1907 and 1908, the years that [Demant Hatt] was in Swedish Lapland. And so, it was really hard. The words weren’t in dictionaries, so I had to ask people. Google is actually incredible. I don’t know how I was a translator before the internet came along, because with Google, you can ask all kinds of questions and often images come up. So, you know, “what does a Sámi tent look like?” You’ll get an answer right away. But I did still have to go through a lot of old books and look at diagrams of how the tents were constructed, because I sometimes couldn’t figure out what she was talking about. So those are kinds of things that you always encounter with translation, just that you can’t envision it. You have to be able to get a picture in your mind in order to translate something and then explain it. But I also have just gotten better at it, and I know where to look. I was up in Tromsø in January and February this year and spent a lot of time in the libraries there just talking to people. And that was really helpful. Again, you grow up in the United States and just don’t have that context for what all these expressions mean, so, you really have to go to the source, and you have to ask people. There’s a lot you can look up online, but you also have to hear from people, “why do you use this word and not that word?”

This, Emilie Demant Hatt. She is clearly a source of much inspiration for you, you’ve also written a biography about her, plus these translations [“By the Fire: Sami Folktales and Legends.”] Can you describe what it was like when you first learned about her, and what it is about her that interests you?

She was an amazing woman, really ahead of her time. She grew up in a middle-class home in Denmark and then was one of the first women to go to art school in Copenhagen, at a time when they had only started admitting women in the 1890s. She’d always had it in her mind that she wanted to go and live with the Sámi, with the nomads for a year. She was sort of the first European woman and probably the first European to actually accompany the Sámi on their spring migration over the mountains from Sweden to Norway, which was a really grueling, rugged track that went on for about two months. So, I was fascinated with her the first time I heard about her, which was on my long trip in the north in 2001. I couldn’t find very much written about her at all, but it started a long pilgrimage for me to visit Denmark to see her paintings and sort of bury myself in archives to bring her to light.

How do you maintain the original author’s voice and intent when translating their work?

You can’t do a literal translation. You have to take the author’s words in and feel them, and then you write it in your own language. You also have to set your tone to the era and the place. You can’t translate an older book into contemporary America American idiom, it just wouldn’t sound right. So, you don’t use contractions, and you don’t say “this guy,” or “this dude.” You can’t use the language that you speak every day, you have to find the tone of the era. One of the ways you do that is by becoming familiar with other books that were being written at the time. You have a lot of choice as an English writer and speaker because our vocabulary is so much larger than Norwegian or Danish. They’re quite restricted, actually. If you ever look in the dictionary, any kind of word that you’re looking up will have 10 English definitions, whereas the Norwegian word is just “good” or “surprising” or “thrilling.” In our thesaurus there are just lots of lots of choices. And so, as a translator, you’re always thinking, what’s the best choice? Norwegian uses the same words over and over again, and that just doesn’t sound right in English, you have to vary it. It’s an interesting challenge. It’s not exactly their voice, because that’s not exactly what they said since they didn’t have those words available to them. So, you kind of help create a voice for them in English.

How do you approach the responsibility of presenting Sami culture accurately and respectfully in your work?

That’s a great question, because it is a responsibility. I think that I’ve tried to educate myself as much as possible, both through reading and through getting to know Sámi people, and a variety of Sámi people. I have spent a lot of time over the last 20 years in Scandinavia, and I’ve gotten to know a number of people and had a lot of conversations. I’m not a Sámi and I don’t have Sámi background, so there are lots of things that I can only understand through the people that I meet. One of the ways I’ve chosen to look at Sámi culture is with the eyes of an outsider, because I am an outsider. So, the first things I began to write about the Sámi were from my perspective as a tourist and a journalist. Back when I was in the north writing for my travel articles, and also for “Palace at the Snow Queen,” I positioned myself as an interested outsider. My goal was to translate what I was hearing from the Sámi people, like a woman reindeer herder, or a man who organizes the Indigenous Film Festival in Finland, or a journalist who saw me in Norway. I would talk to them in English and Norwegian or Swedish, and then accurately write down what they had said to me, as well as the description of our surroundings. And then I presented that. And so, in that case, I’m being responsible as a journalist. Other times, like with my newest book “From Lapland to Sápmi,” I’m going back into the archives. I’m not just looking at the Sámi as victims or as people who had their things taken away from them, I’m examining a reciprocal kind of relationship with the people who collected. Sometimes it was very much appropriation, it was colonization, it was the Swedish state or the Norwegian clergy missionizing and taking away the sacred drums. But other times, the Sámi were selling things to the museums they had professional relationships with as writers, journalists, and artists. So, I’m kind of trying to give a sense of the collaboration and the companionship, as well as the appropriation aspect of these objects. I feel like I’m a partisan for the Sámi and I’m generally on the side of the Sámi, but I’ve also tried to remain objective and explain to the English-speaking or American audience that this is a really complicated question, how all this material got from the north where it was used in Sápmi into the museums. Every step of the way, I think I do feel some sense of responsibility and ask questions like, “am I getting this right?” “Am I understanding this?” I do a lot of reading, and I have asked Sámi people to read my work as well, to tell me what they think. Sometimes they say, “this is great,” and sometimes they say, “no, you didn’t quite understand this, or you got this wrong.” That’s all part of what writing and journalism is, just trying to be true to what you are seeing but also let the people you’re interviewing speak and have their voice too.

You said you’ve met a lot of Sámi people and have had personal relationships with some of them, even having them read your work. Can you recall a particularly inspiring story or moment with one of these people, or a story they’ve shared that really stands out to you?

I got to know a woman named Lillemor Baer up in Kiruna, Sweden, who is a reindeer herder. She was an activist in Kiruna, trying to get people to understand that dog sledding is actually harmful to the reindeer herds. I was sort of curious in this story at first, and someone said, “Oh, talk to this woman, because she’s giving away leaflets trying to explain it.” [When I met her] I felt like we made a good connection beyond just me asking her questions. In the following years, when I came back, I always visited her, and we had meals and went shopping and she drove me around. And that was really important to me. I felt really honored that she had allowed me into her life a little. I have so much more of an understanding of what it’s really like to be a reindeer herder because of her. I was in touch with her again when I was writing a new afterword to my reprint of “Palace of the Snow Queen.” In the afterword, I’m focusing a lot on the environmental struggles that are going on up in the north, the mining and resource extraction. A lot of that is actually coming at the expense of the Sámi, so I wanted to hear her take on that. And it was really good to be in contact with her again. She’s someone who was really important to me.

There’s another person [who helped with] my most recent book, and her name is on the back cover, Káren Elle Gaup. She is a curator at the Norwegian Folk Museum in Oslo. She was really important in the transfer of material from the Folk Museum up to the museums in Northern Norway, the Sámi Museum. I met her about seven years ago in Oslo, when they were just at the start of figuring out how to transfer half of the things in the Sámi collection to the Nordic Folk Museum. I spent some time with her and we talked and walked around the museum. I felt at first when we met, she was cautious, like a lot of Sámi people are, because they don’t really know who you are, where you come from, what use you’re going to make of their stories. And so, what I usually do is start talking about people we might know in common, and I find that then they can start placing me better, even if they haven’t read my work. It begins to make more sense to them why I’m interested in this, that I’m going to try and be fair and convey [their stories] to a larger audience. So, she ended up being important to me in the writing of “From Lapland to Sápmi,” because she read my chapter, and it’s really complex. I don’t think I could have had such a good understanding if she hadn’t read my chapter in a very detailed way and said “no, that’s not right, this is how it was, and this is what we’re trying to do.” She corrected a number of important things.

Can you describe the impact you have seen your work have on others, whether Sami people or people here in the U.S.? What feedback have you received that has really encouraged you as an author?

Well, I wish I could say that it was completely transformative to people in the United States, but I still think that there’s a lot of work to do to get people to think more about the Sámi as part of Scandinavia. To me, it kind of seems like a no brainer. If you’re interested in Scandinavia, you should be interested in Sámi, because they’re very much a part of the history and the culture. Many Norwegian Americans are very patriotic and have lots of happy memories of the old country. That’s all true, I mean, I think Scandinavia is wonderful, that’s my heritage too. But I also think that it’s really important to know as much about the Sámi experience as possible. To the extent that I feel like I have contributed to that discussion? I mean, I’m really one of the few people writing about it regularly, outside of universities. I think a lot of people have been grateful, and they have told me that they’re grateful, because they really enjoy hearing and learning more about the Sámi, and when they have traveled to Scandinavia, visiting some of these places that are associated with the Sámi. There’s also a large contingent of people who are Sámi American—they estimate there may be as many as 30,000 in the United States. Many of them were not told about their heritage. When their relatives came over, they often had been discriminated against in in Norway, so it was a chance for them to lose some of that shame and sense of humiliation, and they just said, “I’m Norwegian,” or “I’m Finnish” or Swedish. So, younger generations, they’re thinking now, “Wow, this is really cool, that my relatives were Indigenous,” and they want to know more about it. A lot of people in that community have turned my books as a way to understand what their ancestors went through, and how they can reconnect with that heritage. So that’s actually really interesting and gratifying to me, too. I hadn’t necessarily thought that that would be an audience, but it’s a big audience.

If you are at liberty to say, could you share any future projects or books you are working on that continue to explore and celebrate Sami culture?

Right now, I’m translating a huge book, its 680 manuscript pages of Sámi folktales that were collected in northern Norway, which will be published by the University of Minnesota Press probably two years from now. I think that it will be a big contribution, because [the Sámi] have an oral culture and a lot of these stories are not well known, but they form a huge part of Sámi culture and contribution to world literature. So, I’m excited about that. They were collected and published originally about 100 years ago in Norway, and they have been reprinted in a condensed form in Norway since then. But they have never been translated in English before, so it’s a big project, and I’m excited to be working on it. I’ve also been speaking with people in Sápmi, mostly women writers who are writing children’s books. There’s a big push to reclaim the Sámi languages, so the Norwegian state and the Sámi parliament are contributing money to getting a lot more books in print that are written in Sámi, especially books for kids because there are now kindergartens and Sámi immersion schools that need material. I think some of that would be really fun to translate, to do some kids books from Sámi to English. So, I’m hoping to do a little bit of that as well.

Celebrate Sámi National Day

Join the celebratory spirit of Sámi National Day on Feb. 6. The historic day marks the very first meeting of the Sámi Congress in Trondheim, Norway, in 1917. Towns often celebrate by raising the official Sámi flag, a bright rendering of red, green, yellow and blue, containing two half circles which represent the sun and the moon. Commemorate the day by reading from one of Barbara Sjoholm’s books—a great way to educate yourself on the rich culture of this Indigenous group, which is still thriving all across the world today.